On This Day in 1964 – The Last Executions In Britain.

Being an abolitionist myself, it’s with some small satisfaction that we’re going to look at Britain’s last executions. To the minute, if you happen to be reading this at 8am. On August 13, 1964 Gwynne Evans and Peter Allen took their unwilling place in British penal history as the last-ever inmates to suffer the ‘dread sentence’, be taken to one of Her Majesty’s Prisons and keep their date with the hangman.

Well, hangmen, actually. Evans paid his debt to society at HMP Strangeways at the hands of Harry Allen (grandfather of comedienne Fiona Allen) assisted by Harry Robinson. Allen paid his at HMP Walton at the hands of Scottish hangman Robert Leslie Stewart (known as ‘Jock’ or ‘The Edinburgh Hangman’) assisted by Royston Rickard.

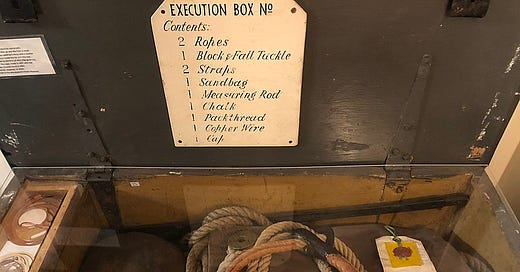

Their crime was unremarkable (not that any murder is a trivial matter) and their executions were equally standard affairs except for the fact that they were the last in British penal history. Judges would continue to don the dreaded ‘Black Cap’ and pass the ‘dread sentence’ until 1969 (the 1970’s in Northern Ireland). The death penalty was retained for several crimes other than murder until 1998 and its final repeal under the European Human Rights Act. But the noose and scaffold had already been consigned to history and the occasional prison museum.

Never again would the prison bell toll or the black flag be hoisted just after eight or nine in the morning. No longer would crowds gather outside a prison’s gates in protest at what was happening inside.. No more would a prison warder have to brave an angry crowd to post the official announcement on a prison gate. After centuries of State-sanctioned killing ranging from the deliberately-barbaric to the scientifically-precise, ‘Jack Ketch’ had finally put away his noose and passed into history.

Not that this was any consolation whatsoever to Evans and Allen. As far as they were concerned it made no difference at all and nor did it to anyone else. They still had to sit in their Condemned Cells at Walton and Strangeways, guarded 24 hours a day by prison warders and hoping every day for a reprieve that never came. Prison staff and the hangmen still had to report for duty as instructed and ensure that everything was prepared properly down to the finest detail.

The Appeal Court judges and Home Secretary still had to discuss, debate and ponder their decision, knowing all the time that if they refused clemency then these two deaths would be as much their responsibility as that of the executioners themselves. The families and friends of the condemned had no easier time than the condemned themselves. Allen and Evans would die, but their friends and families would still have to live with that afterwards.

Their crime was brutal, their guilt undeniable. Given the evidence against them there was almost no chance of their being acquitted. To manage that would require lawyers possessed of both boundless talent and equal optimism. If they did ever stand a chance of avoiding the gallows then it was far more likely to be through a reprieve than an acquittal. Barring a reprieve or a legal blunder serious enough to impress the Court of Criminal Appeal, their race was run. They probably knew it.

Evans and Allen were both typical, garden-variety condemned inmates. Under-educated, lower IQ’s than usual, failed to hold down any job for very long and with a string of petty criminal convictions between them. Fraud, theft, deception, the usual type of relatively low-level crimes that see a person in and out of trouble on a semi-regular basis, but nothing to suggest that either was capable of brutal, cold-blooded murder. Then again, a great many brutal, cold-blooded murderers have been described as not being ‘the type’ even though there’s no ‘type’ to watch out for. It would make the lives of honest people and detectives so much easier if there were.

Aside from not seeming the type, Allen and Evans weren’t exactly criminal masterminds either. After beating and stabbing to death Alan West in his home during a bungled robbery on July 7, 1964, Evans in particular left a trail of evidence that Hansel and Gretal would have been proud of. He left a medallion at the crime scene with his name inscribed on it. When he was dumping the stolen car used in the crime Evans dumped it at a local builder’s yard. He’d made himself so conspicuous (and, to a neighbour, highly suspicious) that it wasn’t long before he found himself in custody. Being found in possession of the victim’s gold watch probably didn’t help his case either.

Once under questioning Evans excelled himself even further. Initially he denied being involved. On realising he’d left a smoking gun with his name on it at the scene he decided to bury Peter Allen. To save himself from a charge of capital murder he’d put all the blame on his accomplice. Evans denied having a knife during the robbery and clearly blamed Allen for stabbing West to death. His ploy might have worked a great deal better but for one small problem; Evans’s own big mouth.

Being keen to bury his crime partner and possibly save himself, Evans talked loud and often. A little too loud and often as it turned out. Evans was loudly denying his having had or used a knife to murder Alan West. It was then that police pointed out to him that they hadn’t actually mentioned a knife, nor had they released that information to the press.

Allen was now also in custody and being questioned. Both killers were under lock and key within 48 hours of committing their crime, a pretty fast resolution to a murder investigation. By modern American standards, their road from trial to execution would certainly seem faster still. One of the principle complaints of America’s pro-execution lobby is that the appeals process takes far too long. There are too many levels of court, too many technicalities, too many bleeding-heart pro-bono lawyers, too many soft judges and State Governors who refuse to allow what a judge and jury have already decided to hand down.

While it’s still groused about in the US, it was never the case in Britain. A condemned inmate was granted a minimum of only 3 Sundays between sentencing and execution. That didn’t mean an execution always happened 3 weeks after a sentence due to appeals, finding new evidence, court schedules, sanity hearings and so on, but 3 Sundays was all you could expect as of right. Miles Giffard, hanged at Bristol in 1953, spent only 18 days between sentencing and execution.

After sentencing the judge would often send a private, highly confidential, report including their opinion on whether a prisoner should be reprieved. Their reports weren’t always heeded, but they had more influence than any other factor in deciding whether prisoners lived or died.

Avenues for appeal were both smaller in number and moved a great deal faster than their American counterparts. After sentencing the first stop was the Court of Criminal Appeal. Appeals against conviction and sentencing were heard by a panel of 3 judges, often including the Lord Chief Justice unless they had presided at the trial in question. If they rejected the appeal the next stop was the Home Secretary (nowadays the Minister of Justice). If the Home Secretary refused clemency the case file would be annotated with a single phrase;

‘The Law must take its course.’

Prisoners could still appeal to the King or Queen, but this was effectively pointless. By one of the many unwritten rules so beloved of British officialdom, the Monarch didn’t grant appeals except on the private advice of the Home Secretary. A sitting Home Secretary (also a Member of Parliament so an elected official) might not want to defy public opinion by granting a reprieve while risking their seat at the next election.

The Monarch, on the other hand, not having to consider their approval rating, could grant an appeal thereby saving a prisoner without causing problems for the elected officials concerned. But, regardless of whether a prisoner appealed directly to a Monarch, without a Home Secretary’s advice there would be no reprieve. Nobody involved felt merciful towards Evans and Allen.

Their trial began at Manchester Assizes on June 23, 1964 with Mr. Justice Ashworth presiding. Leading for the prosecution was was Joseph Cantley, QC (Queen’s Counsel, a senior lawyer) while Allen was defended by lawyers F.J. Nance and R.G. Hamilton. Evans was represented by Griffith Guthrie-Jones, QC. It didn’t take very long. Even the best of defenders couldn’t have won a verdict of not guilty. With Evans’s many and varied blunders he was effectively doomed from the start. Allen’s wife was the star prosecution witness, testifying that she’d seen Evans dispose of the knife and that Allen had made incriminating remarks in her presence

Not surprisingly both were convicted. As their murder was committed during a robbery it qualified as capital murder under the 1957 Homicide Act. This Act, brought in after the 1955 execution of Ruth Ellis, drastically altered capital punishment in Britain. It clearly defined the difference between capital and non-capital murder, dispensing with a mandatory death sentence and allowing judges, prosecutors and juries some discretion.

Before the 1957 Homicide Act jurors in particular were quite limited in their options. They could acquit a defendant, find them guilty but insane (avoiding a death sentence), guilty with a recommendation for mercy or simply guilty as charged. For non-capital murder life imprisonment was the sentence. If convicted of capital murder the sentence remained death.

The Act also enshrined diminished responsibility into English law for the first time, largely a response to the Ruth Ellis case. This wasn’t done to limit the number of executions per year, but to ease the minds of jurors in particular. It was hoped that their consciences would be less troubled when considering a guilty verdict if they knew that a death sentence had been the legally correct decision. It was also hoped that they wouldn’t acquit a guilty prisoner rather than know a mandatory death sentence was the result of their decision.

In practice, though, it meant very little. A jury’s recommendation for mercy carried far less weight than the trial judge’s confidential report. Judges were usually consulted in capital cases regarding the trial and especially the prisoner. If they recommended mercy then they had a very good chance of securing a reprieve as, in the twentieth century, only around half of the death sentences passed were actually carried out.

Notable exceptions were those who used poison or firearms who (unofficially, anyway) could seldom expect a reprieve. It has been suggested that an unwritten rule existed for poisoners and shooters; If they used either method they were not to be reprieved unless (as in the case of pregnant women) the law demanded it. This has never been officially admitted as to admit it would make Britain’s death penalty seem even more arrbitrary than it already does.

With Evans and Allen convicted of capital murder Justice Ashworth then took his own place in British penal history, becoming the last British judge in a British courtroom to don the dreaded ‘Black Cap.’ The cap was actually a square of black cloth, usually silk or velvet. Placed atop a judge’s wig by the Clerk of the Court, it was a gesture of mourning for the newly-condemned. The Judge would then recite the death sentence which had been modified a few years earlier. Incidentally the Black Cap remained part of a judge’s ceremonial regalia long after Britain’s executiners had been retired.

Previously, the judge would have recited a long, drawn-out set script which usually did little to help a prisoner keep their composure. It usually went something like this:

“Prisoner at the Bar, you have been convicted of the crime of wilful murder. The sentence of this Court is that you be taken from this place to a lawful prison, and thence to a place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead. And that your body be afterwards cut down and buried within the precincts of the prison in which you were last confined before execution. And may the Lord have mercy upon your soul. Remove the prisoner…”

Ashworth’s version was edited for brevity and out of compassion for the prisoners hearing it. No longer did the executed have to be buried within prison walls and the length of the speech was hard on everybody, especially any prisoner unfortunate enough to be standing in the dock at the time:

‘”Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans, you have been convicted of murder and shall suffer the sentence prescribed by law.”

Shorter, certainly. Any sweeter? Probably not by much. Their one mandatory appeal was heard by Lord Chief Justice Parker, Justice Winn and Justice Widgery on July 20, 1964. It was denied the next day. The executioners were engaged and a date set. Evans and Allen would die at HMP Strangeways and HMP Walton respectively. Harry Allen and Harry Robinson would execute Evans, Robert Leslie Stewart and Royston Rickard would execute Allen. Both men dying at the same time meant that no one hangman could ever claim to Britain’s last executioner, despite Allen being far senior to Stewart.

After Allen and Evans more death sentences would be passed. More invites would be sent to the progressively-dwindling number of executioners on the confidential ‘Official List’ held by the Prison Commissioners. More prisoners would spend anxious days and nights until their reprieves arrived, which they inevitably did. After Evans and Allen a moratorium of five years was declared during an at times very heated debate. In 1969 the death penalty for murder on the British mainland was abolished by Parliament.

Northern Ireland retained it a while longer but the gallows at Crumlin Road Prison, last used to hang murderer Robert McGladdery in 1961, was never used again. One by one, the old gallows rooms and condemned cells were demolished or repurposed. The exceptions were Wandsworth Prison in London and Devonport Dockyard in Devon. Wandsworth’s, the last remaining gallows for civilian use, was finally removed in the late 1990’s.

The death penalty for other capital offences (arson in a Royal dockyard, treason and piracy) also disappeared, although military offenders could still have been hanged unil 1998. In that year permanent, full abolition was finally enshrined in law. The lights in Wandsorth’s ‘Condemned Suite’ would never burn again.