On This Day in 1924 – Howard Hinton, Georgia’s first electrocution.

The first, but far from the last.

It’s common to find ‘Peachtree Bandit’ Frank Dupre (armed robber and murderer executed on September 1, 1921 with Luke McDonald) listed as the last man to hang in Georgia. He wasn’t. That was Arthur Meyers, a murderer hanged at Augusta on June 17, 1931 for a murder committed in March, 1924. McDonald, despite dying with the notorious DuPre, seldom gets a mention in accounts of DuPre’s case.

Notoriety guarantees attention while mediocrity does not. Many Georgians remember John Wallace of ‘Murder in Coweta County’ infamy, they seldom know of Jimmie Richardson who died minutes before him. Wallace was wealthy, white amd the first white man in Georgia electrocuted on te word of African-American witnesses Robert Lee Gates and Albert Brooks. Richardson was poor and, to many, a typical case who murdered his former partner. Wallace and Dupre are well-remembered. McDonald, Meyers and Richardson (and especially their victims), not so much.

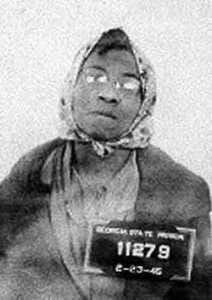

It’s equally common for the same reports to list a ‘Howard Henson,’ electrocuted on September 13, 1924, as the first Georgian to ride the lightning. He wasn’t, his name was actually Howard Hinton. Hinton was executed for rape and robbery or, to put it more delicately, ‘assaulting a white woman.’ Hinton (1920’s Georgia being 1920’s Georgia) was also an African-American.

So, with that in mind, why the confusion? The Georgia Assembly, thanks in part to Dupre’s execution, had passed a law on August 16, 1924 changing the State’s method from hanging to electrocution and removing tthe responsibility from individual counties. Anyone condemned after that was headed for the Georgia State Prison Farm then located at Milledgeville. The change was not for everybody, though. Those already sentenced to hang would still face the gallows operated by their resident County Sheriff.

Before Hinton walked his last mile at Milledgeville, James Satterfield and Harrison Brown still faced the rope. After Hinton, Warren Walters, Gervais Bloodworth, Willie Jones and Mack Wooten also kept their dates with the hangman. Not until Meyers was Georgia’s gallows finally consigned to history, by which time there were six more hangings and 66 electrocutions.

Georgia’s method had changed. Its procedure had changed even more. Instead of County Sheriffs doing this grim task the Warden at Milledgeville now became Georgia’s only official executioner. Granted, County Sheriffs would occasionally still hang somebody, but Milledgeville’s Warden would be throwing a switch.

County Sheriffs were relegated to a supporting role, escorting their condemned to Milledgeville between twenty and two days before their scheduled date of execution. At Milledgeville the Warden would be assisted by a qualified electrician, two doctors, a guard and two assistant executioners. The condemned could also have their lawyers, relatives, friends and religious representatives with them when their time came.

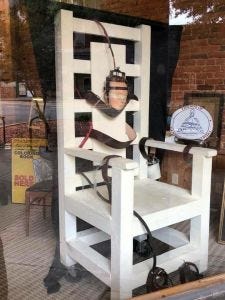

Appropriated on August 27, 1924, Georgia State Prison’s new death chamber cost $4760.65. The change had also been overwhelmingly endorsed by the state’s House of Representatives voting 115 to 45 in favour with 46 abstentions. It hadn’t been universally approved, though. Milledgeville is located within Baldwin County and Baldwin Representative J. Howard Ennis wasn’t happy.

Echoing the concerns raised decades later by Marvin Wiggins, Superintendent of Mississippi’s State Penitentiary at Parchman in Sunflower County, Ennis decried the idea of Baldwin being known as the ‘Death County’ if executions there became a permanent feature. It did no good. Just as Wiggins was later ignored in Mississippi, Ennis’s pleas met deaf ears in Georgia. Wiggins would be saddled with Mississippi’s gas chamber, replacing the state’s portable electric chair in 1954. Ennis was saddled with the chair permanently sited in Baldwin County.

Like it or not, Old Sparky had come to the Peachtree State and was there to stay. As Georgia’s County Sheriffs had once plunged their inmates into eternity, Milledgeville’s Warden would offer Georgia’s condemned a new form of Southern hospitality;

A short walk and a comfortable chair.

Sparky’s reign in Georgia would be longer than in Missisippi if equally inglorious, ending with murderer David Loomis Cargill on June 9, 1998. Ennis also got his way. The chair remained at Milledgeville only until 1938. After 14 years Willie Daniels provided its farewell meal before moving to the new Georgia State Prison at Reidsville in Tattnall County. Daniels, already Georgia’s 162nd electrocution, died on December 27, 1937.

At Reidsville business was even more brisk. 256 inmates (including the now-exonerated Lena Baker, John Wallace, Jimmie Richardson and many, many more) met their ends. First was murderer Archie Haywood on May 6, 1938. The last was murderer Bernard Dye on October 16, 1964. Sparky wouldn’t be put to work again at Reidsville. The original chair was retired and replaced with a similar device. Executions also moved to the euphemistically-named Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center in Jackson in June, 1980. Georgia would have to wait three years to christen Son of Sparky, itself now on display at Reidsville which closed in 2022.

The new chair debuted on December 15, 1983 when murderer John Eldon Smith suffered Georgia’s first execution in almost 20 years. Just like Hinton in 1924 he was far from being its last. Until May, 2001 when Georgia replaced bottled lightning with bottled poison, another 22 convicts were seated, strapped, capped and killed. In October of that year the Georgia Supreme Court finally pulled the plug completely. Already replaced by the needle, the electric chair was now officially ruled to be a cruel and unusual punishment. By the time the chair became history it had taken 440 men and one woman with it.

It’s sobering that Arthur Meyer (Georgia’s last to hang) and Howard Hinton (its first to be electrocuted) were both African-Americans. It’s even more sobering to consider that the majority of Georgia’s executions, regardless of method, have been non-white. It’s also unfortunate that Milledgeville wasn’t just the first place in Georgia to see an electrocution, but also the first capital of the Southern Confederacy. Working together, Jim Crow and Jack Ketch have cast a long shadow.

"Working together, Jim Crow and Jack Ketch have cast a long shadow."

True. This is chilling. Even seeing that electrocution chair makes me a little sick.